Come By Here | A Story about Belonging

A Sacred Text for Black Folks

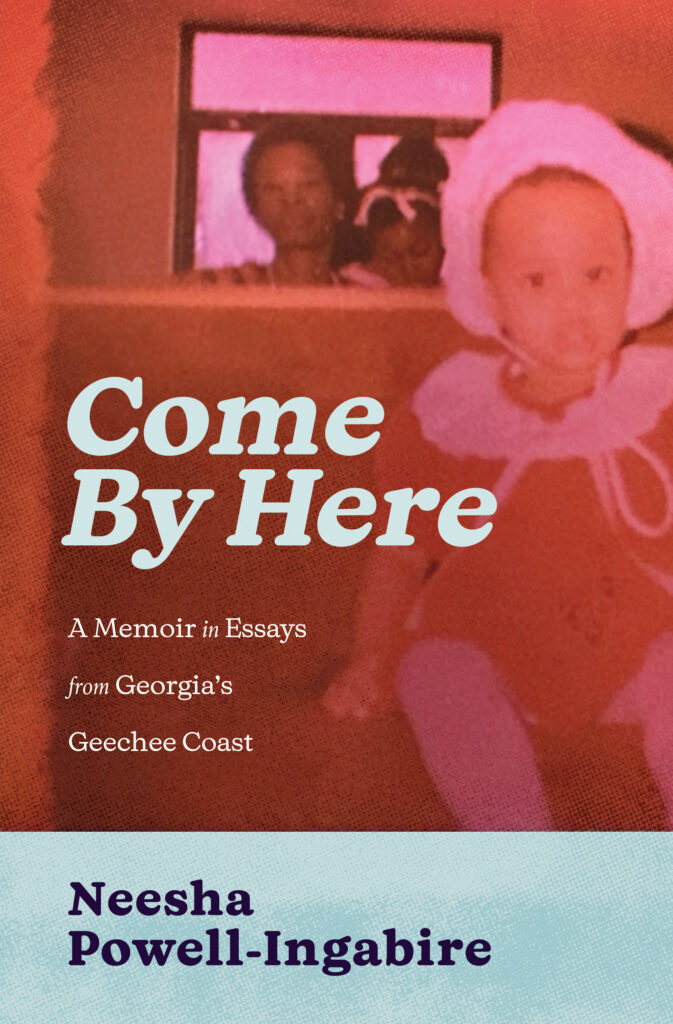

When I first began reading Come by Here: A Memoir in Essays from Georgia’s Geechee Coast by Neesha Powell-Ingabire, my first thought was: this book is a sacred text for Black folks of and from the Gullah Geechee Corridor. I started buying up copies directly from the publisher, much like Oprah did with The Color Purple, and sending them to Black women I know to remind them: you belong.

Growing up, my granddaddy always said the word “Geechee” with a negative connotation. There was a gruffness in his voice, a slick undertone, that made it clear it wasn’t meant as a term of endearment. It was used to cut people down. He’d often call one of our Miami cousins “Carolina Geechie” to mean he was less than, ignorant, backwoods/country, or “slow.” It’s a word that has carried a heavy, complicated history, layered with both pride and pain, reclamation and rejection.

I don’t know Neesha personally. I’ve never met her or even heard of her, truthfully. But she feels familiar, like someone who has walked down paths similar to mine. This memoir, in its honesty, vulnerability, and depth, is the first text I’ve ever read about my hometown—and I hope it won’t be the last. More of our stories—Black firsthand accounts—deserve to be told. Whether we call ourselves Gullah or Geechee or something else entirely, our stories deserve to be told.

Brunswick: Is Home

It’s impossible to read this text without acknowledging my own history with Brunswick, the place I call home. I arrived here when I was just three days old, on a Greyhound bus with my mother. We came to my great-grandma Lila’s house on US Hwy 82 in Brookman, a community deeply rooted in the descendants of the enslaved. There, I was embraced by aunts, uncles, cousins, and godparents—people who surrounded me with love and taught me, from the very beginning, that I belong.

Brunswick has always been more than just a place to me. For me, Brunswick is home. There is no place on Earth where I feel more connected than along the coast of Georgia and Florida. It’s also where I found my grounding, my community, and my resistance. For many, Brunswick is seen as a place where people come to die—physically, mentally, spiritually, and emotionally. But for me, it’s always been a place to live. A refuge that has safeguarded me, nurturing me as I returned to the world to do the work I am called to do.

Brunswick is where I learned the meaning of Community Rx and Soul Work Rx. It’s where I came to understand the transformative power of coming together.

The Chapters That Stayed With Me

A Rolling Stone / Papa Was

My favorite chapter was A Rolling Stone/Papa Was. Neesha humanizes her father in a way that’s rare in narratives about Black men.The chapter was especially moving because it humanized her father in a way that Black men often aren’t allowed to be in literature. I cried reading about the ways PTSD and single parenthood shaped their relationship. It reminded me of the importance of holding space for the fullness of Black men’s stories.

A Brush With Magic or An Ode to Mrs. Cornelia (Walker-Bailey)

A close second favorite, was A Brush With Magic Or An Ode to Mrs. Cornelia (Walker-Bailey) it’s worth buying the book for and reading on its own. The heartfelt acknowledgment and the continued amplification of awareness about the degradation of both the land and its people, alongside the enduring beauty of Sapelo, are vital. It stirred something deep within me, urging me to reclaim and buy our land back. Spirit sent me instructions after reading it.

Facts of a Black Girl’s Life

The bravest chapter, Facts of a Black Girl’s Life, names the harm Black girls endure within the very communities meant to protect them. It’s raw, honest, and an necessary act.

Family Dynamics and Black Women’s Experiences

Neesha’s exploration of family dynamics felt like she was speaking directly to my own life. Her intergenerational relationships with her mother and grandmother mirrored the generational bonds in my family. I found myself nodding along as she unpacked the complexities of those connections.

The juxtaposition of Pain as memory

The sections recounting Ahmaud Arbery’s murder were heavy. I almost skipped them, not wanting to relive the pain. I experienced it in real time, every day, and reading about it brought it all back. Yet, it needed to be told.

What saddens me most is how people only seemed to care about Brunswick when it became fashionable to do so. They co-opted the pain of this place without ever truly returning to it—not unless they had no other choice.

Text is intimate and maybe even gaslighting?

Reading the names of people I know, like my dear friend Rachael Thompson, and recognizing others in passing, like Aminata Traore-Morris and Matthew Raiford, added an intimate layer to this text. It’s one thing to hear about these places and people; it’s another to actually know and see them documented. It also makes you question what you know as true.

Environmental and Health Injustice

Her analysis of Black maternal health in relation to Brunswick’s toxic environmental legacy struck a hard nerve that I wasn’t sure how I wanted to process beyond the lack of solutions. But here is what the text says directly:

The Hercules/Pinova site “contains mercury and polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), which primarily affect people of childbearing age, children, and fetuses. They may cause lower IQs, a weakened immune system, and behavioral and psychological effects in children, and may cause thinning of the uterus lining, possibly leading to the need for its removal. Upon studying the rates of hysterectomies in Brunswick, GEC’s founder discovered that he could correlate the rate of hysterectomies in the city to a population that has been heavily exposed to PCBs.”

These words confirmed suspicions I’ve long held but never had validated. It’s heartbreaking to see how systemic racism and environmental negligence have left generational scars on our community.

Representation and Naming Matter

The chapter analyzing McIntosh County’s Black community was particularly fascinating, sparking my own curiosity. I loved the way Neesha addressed the white author of Praying for Sheetrock(I LOVE WHEN WE GET IN WHITE FOLKS A** not sorry), calling out the ways white people often co-opt and commodify Black stories. Still, I wish she had mentioned Dr. William Collins, whose work on genealogy and archival photos of Black families is so critical, or the Lotson family or figures like Commissioner Charles Jordan (IYKYK) and so many more I know she can’t name them all.

What moved me most was seeing Reverend Nathaniel Grovner and Samuel (My beloved “Mr. Sammie”) Pickney highlighted as civil rights heroes. I never knew that about them.

A Few Critiques and Questions Raised

Parts of the book felt like an unedited brain dump. There was repetition, but I understand this is often the nature of essay collections. The format allows readers to engage with each chapter independently, but it sometimes disrupts the narrative flow.

And although I loved the chapter about the Gillyard Family Farms and the importance of the oral history shared, I expected more of Brunswick’s Black history to be highlighted. Amy Hedrick’s work in Glynn County through GlynnGen and Jason Vaughn’s Black history work is especially of note and could have been referenced.

I know enough to know I want to know more.

Still, the book raises essential questions: Who gets to call a place home? Who does home belong to, if not all of us?

Lessons and Final Reflections

This memoir reminded me of the critical need for Black stories to be told by Black voices. It validated how powerful it is to see one’s community and lived experiences reflected in literature. Neesha’s work stands as a counter-narrative to the co-opting of Black stories by outsiders, who often tell them without the nuance, respect, or context they deserve.

It underscored the importance of humanizing familial relationships and keep your boundaries clear, even when they are complicated or painful.

Hold space for collective memory.

I reflected on the idea of home—not just as a physical place but as a repository of memory, resilience, and resistance.

The memoir deepened my awareness of how environmental degradation and systemic racism intersect in places like Brunswick. Neesha’s discussion of health disparities caused by industrial pollution revealed the tangible and long-term effects of neglect and exploitation on Black communities. It’s not just history—it’s a present, lived reality.

This memoir illuminated me of the strength and vulnerability in Black womanhood. Black women get to be the wailing woman. It is necessary, as altar call, as witness, as alarm. We are both messy and magical.

The Complexities and Implications of Belonging

Come by Here– encapsulates something we all long for: belonging.

The memoir taught me about the profound connection between identity, place, and belonging. It highlighted how our histories and environments shape who we are, whether we embrace or resist those roots. Neesha’s exploration of her Geechee heritage felt like an affirmation of the complex and often misunderstood identities that exist within the Gullah Geechee Corridor. This book has many through thread themes about gender, race, and place, but at its root, it’s about community and connection.

And Neesha, I hope you always remember how deeply your grandmother loved you, know your Godmother Aunt Nettie is proud of you, and that you will always belong.